Lately I’ve been wondering a lot about what distinguishes a good developer from a great developer, and when a developer becomes a city-builder.

Last year I was invited by Lendlease’s new Green Utilities division (now branded as Podium) to tour several of their large urban regeneration projects in Sydney (Barangaroo, Darling Square), Melbourne (Victoria Harbour and Batmans Hill), and Brisbane (Showgrounds). We exchanged lessons about the development of neighbourhood-scale infrastructure – technologies, business casing, business structures, barriers, and municipal policy. Of course this being Australia, there was a lot of focus on neighbourhood-scale wastewater treatment and grey water systems, but also district energy (and in particular linkages to co-generation). During the visit, I also had the opportunity to meet with planners from Sydney, Melbourne, and Brisbane. Those cities have all been struggling with the role of district utilities in city building and tackling emerging priorities such as climate change, energy security, and urban resiliency. And they’ve also been trying to figure out the role of cities in developing, promoting, or facilitating those district utility schemes.

Lendlease is a publicly traded multinational property and infrastructure company headquartered in Sydney, Australia. Lend Lease operates in over 40 countries. Well known for project management and construction of very large building projects (one of the most iconic being the Sydney Opera House), Lendlease also has its hands in rental apartment buildings, master planned residential developments, property management, infrastructure development, urban regeneration, real estate investment funds, and public-private development partnerships.

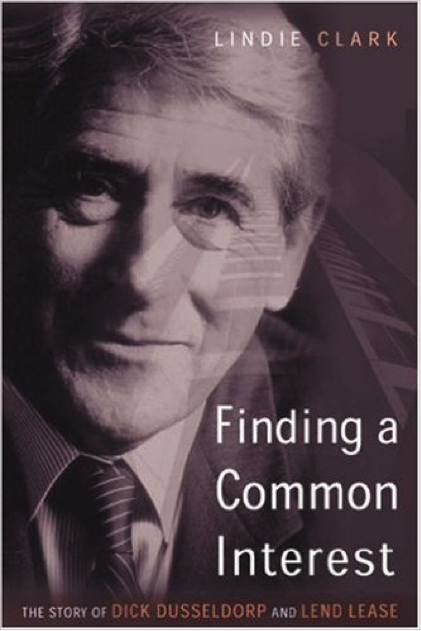

During my visit, I learned about the iconic and mold-breaking founder of Lendlease, Dick Dusseldorp. Although he retired in 1988 and died in 2000, his presence is clearly still felt in the company. My hosts told me about a recent biography about him – Finding a Common Interest. I was intrigued not only based on the clear success of the company he founded, but also by the title of the book. It seemed to capture something important about Lendlease’s corporate culture, and also something important about great development.

Dusseldorp was sent to Australia in 1951 to do business development for a Dutch homebuilder. There he established Civil and Civic as a new arm of his Dutch employer. During his tenure at Civil and Civic he pioneered the principle that the designer should be employed by the building contractor rather than the other way round, an idea that eventually helped Dusseldorp secure the contract to build the podium of the Sydney Opera House in 1957. In 1958, Dusseldorp established Lendlease to finance the construction activities of Civil and Civic, and by 1961, Lend Lease overtook Civil and Civic. From there, the company has grown into a billion dollar property development, management and financial services firm. During his time at the helm of Lendlease, Dusseldorp pioneered many new approaches to production management, labour management, business development, corporate governance, negotiation and community building. He also took an active interest in mentoring youth and developing existing talent.

Dusseldorp was an early pioneer of corporate responsibility, well before the term came into vogue. And it wasn’t just a label or theoretical concept he adopted: Dusseldorp lived and breathed it. And this seems engrained in the company even to this day. It’s refreshing to read a story of corporate responsibility in the form of a biography rather than a theoretical text or a superficial annual report. His biographer describes the essence of Dusseldorp’s philosophy as “consultative co-operation” and the “equitable sharing of the fruits of enterprise” among workers, shareholders, clients and communities. Some quotes from Dusseldorp that capture this philosophy:

“The time is not far off when companies will have to justify their worth to society, as indeed increasingly major public and private investments have to do now, with greater emphasis placed on environmental and social impact than straight economics.” (Dusseldorp’s chairman address in 1972)

“The company’s activities have to be socially relevant – for the simple reason that most concerned people only want to spend their life on such efforts.” (Dusseldorp’s chairman address in 1983)

“There are two things in life. You can be out for the maximum amount of profit you can possibly squeeze from your efforts, or you can aim at a reasonable profit and have the feeling when you retire that you leave something behind.” (Dusseldorp from 1957 cited in Lend Lease AGM 1988)

And some of the tributes after his death:

“He always saw the big picture. He introduced a new dubiousness about what we were seeing in things that we were inclined to accept. Having been convinced that there was a potential better way, we were encouraged to move on to find it… [He] lived his life giving to many people the same message and example: that if we only listen to the world around us and question it a little, then, with application and a sense of social responsibility, we are capable of achieving anything.” (Tribute from Chris Rumsey, CEO of Dusseldorp’s UK-based property investment company Dusco)

“…I grew to understand his approach, to turning what appeared to be insurmountable obstacles into opportunities and innovative solutions. He had long mastered the art of creative thinking: the rare combination of knowledge, obsession and daring.” (Tribute from his son Tjerk)

So what does this have to do with the difference between a good developer and a great developer, or a mere developer and an actual city builder? I think that rests in the simple title of this book – finding a common interest. Great development and city building occur at the nexus of the private and public spheres, in the sense of responsibility, passion and creative thinking of a developer who finds ways to deliver both private benefits and public benefits simultaneously. Win-win solutions realized through great innovation and perseverance. To me, these are hallmarks of great developers and real city builders. We’ve been fortunate to work with developers like these. Stay tuned for some examples.

Trent Berry