New York City (NYC) is the densest and most populous city in the U.S. Not surprisingly, it also ranks among the top cities in the world for greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions on an absolute basis. Direct and indirect emissions from buildings account for approximately 70% of the city’s carbon footprint. This is due in part to the local climate and age of buildings, but also to the relatively high GHG intensity of energy sources used to power and heat buildings in New York State. Therefore, the recent move by NYC to enact a law that aims to cut emissions from existing buildings by 40% in 2030 and 80% in 2050 is critical for the City to achieve its GHG reduction goals.

A Precedent-Setting Move

The levels of emissions reductions by 2030 and 2050 required to meet the goals of the Paris Accord cannot be achieved without starting to de-carbonize the existing building stock. We know we need climate policy for existing buildings, yet cities have been slow to act on this sector. The NYC legislation has been lauded for being one of the first attempts in North America, and indeed globally, to tackle GHG emissions from existing buildings. The law has also been criticized for imposing additional costs on building owners and tenants. Despite the uproar, it appears that the near-term impacts of the prescribed limits for GHG emissions have not received much scrutiny.

What Does the Legislation Mean for the Average Building?

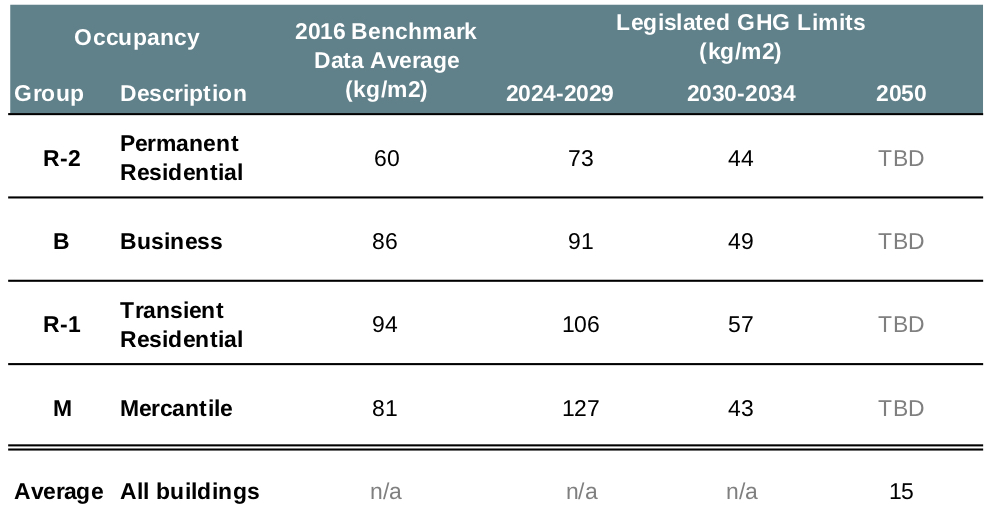

Every year, the Mayor’s Office of Sustainability publishes an Inventory of New York City Greenhouse Gas Emissions, and part of this program is a mandatory energy use reporting program that collects energy use data from large buildings (over 50,000 square feet) throughout the city. This benchmarking program is a treasure trove of data for energy nerds such as myself, and it allowed me to compare the GHG intensities from NYC’s existing buildings to the limits imposed by the new law, described in Intro 1253. The law imposes limits on GHG emissions beginning in 2024 and then ratchets them down significantly in 2030 to achieve the overall 40% reduction target (see table below). At first glance, it might seem that the law would have most building owners scrambling to complete the necessary upgrades in order to be in compliance with the 2024 limits (purchasing renewable energy credits or carbon offsets is also an approved pathway to compliance). However, when I compared the prescribed limits to the reported emissions data from 2016, it was apparent that most buildings will not be affected until at least 2030.

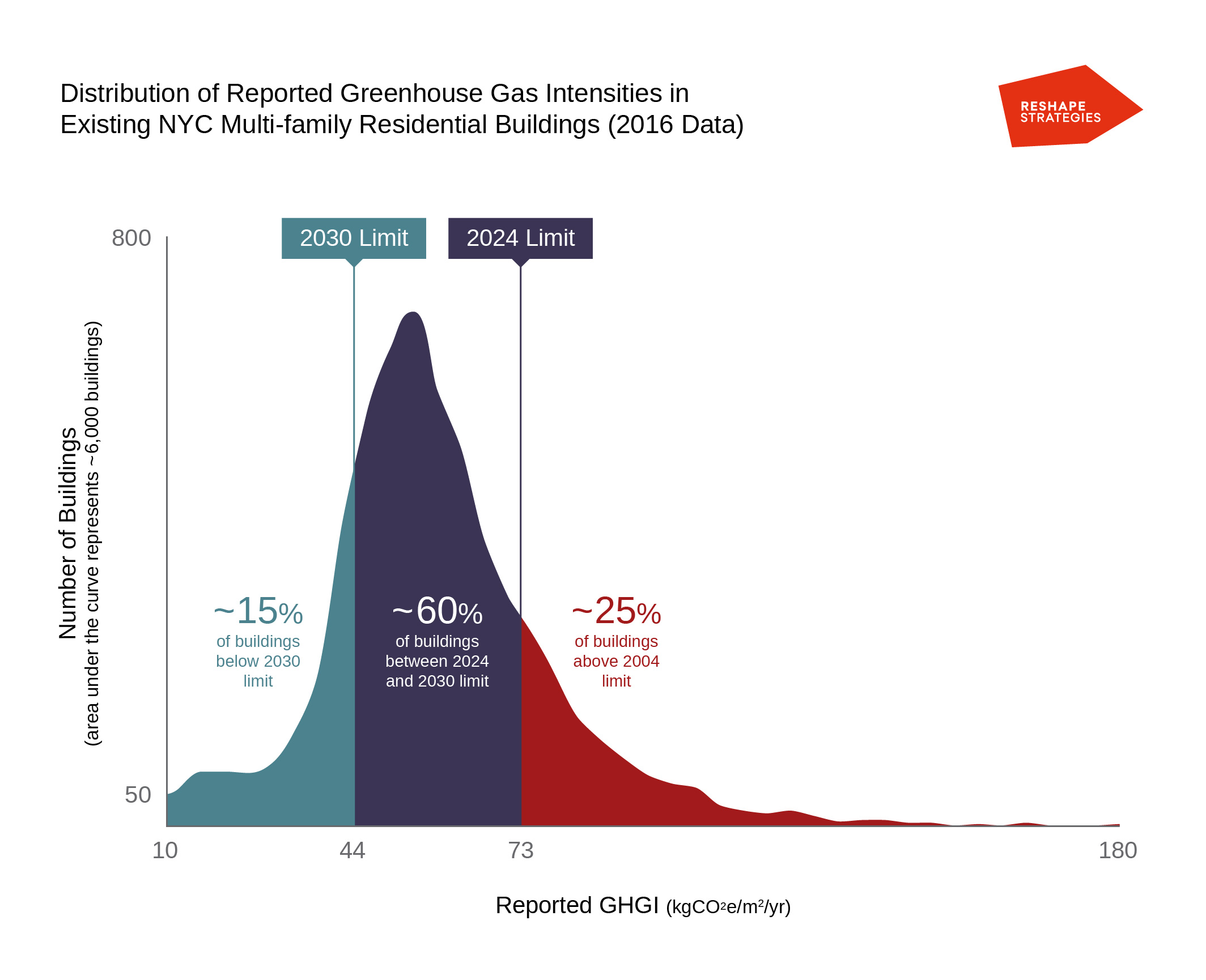

After a bit of data clean-up to remove data gaps and obvious outliers, I plotted the distribution of reported building GHG emission intensities (GHGI in kgCO2e/m2/yr) for each type of building specified in the legislation and compared the data to the limits imposed in Intro 1253. The results of this analysis suggest that the majority of the large buildings in the City are already in compliance with the limits imposed in 2024, and in the case of multi-family residential buildings, only 25% will be required to take action by 2023 to avoid penalties under the new law. By 2029, the percentage of multifamily residential buildings required to take action will rise to 85%. A graph of the emissions intensity distribution for multi-family housing (the single biggest data set, accounting for 80% of the reporting buildings) is provided below to illustrate my point.

While I was initially surprised to find that this celebrated new law was going to have less impact than the headlines led me to believe, it is understandable that NYC has taken a gradual approach to legislating emissions from existing buildings. They have embarked on an arduous path and the law helps socialize the concept of regulating emissions from existing buildings while giving the owners considerable time to plan and adapt.

To achieve the reductions that NYC is prescribing in 2030, many buildings will require major envelope upgrades and mechanical system retrofits. Building owners will need time to plan for and complete these upgrades; local contractors will need to increase their capacity to complete the work; and the City will need to build capacity to support and administer the law. Hopefully the clear direction on emissions limits and the penalties for non-compliance defined in the legislation (US$ 268 t/CO2 for any excess emissions) will encourage building owners to begin taking steps toward compliance with the 2030 limits well before the 2030 deadline.

Policies Must Look Beyond the Building

There are also systemic factors related to indirect emissions that are outside of a building owner’s control, such as the GHG intensity of the electricity supply in New York State and of the Con Edison steam system that serves approximately 1,800 buildings in NYC. Reducing the emission intensities of these energy supplies could be a more cost-effective means of reducing indirect emissions from existing buildings in many cases (as opposed to conservation measures within individual buildings).

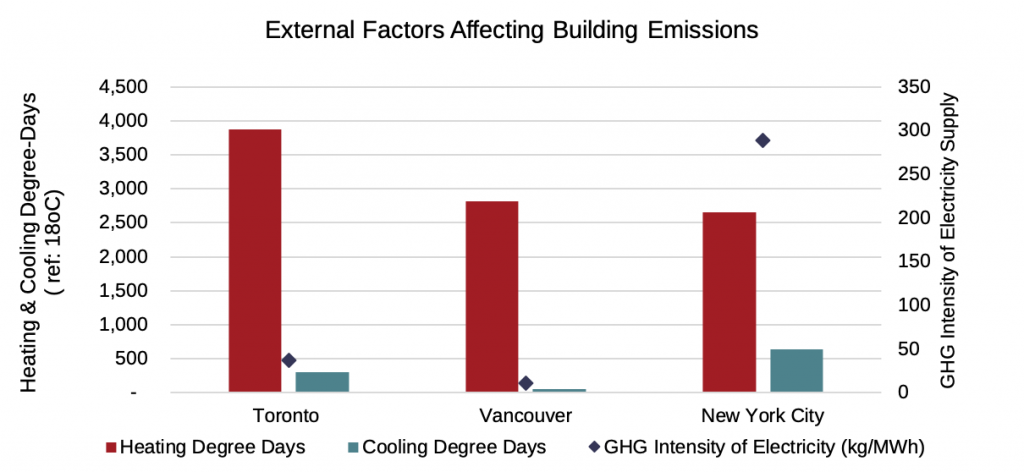

It is eye-opening to compare the 2050 GHGI limit for NYC existing buildings to the limits imposed for new buildings in the Toronto Green Standard and the Zero Emissions Building Plan in Vancouver. The Toronto Green Standard has a 2030 limit of 5 kgCO2e/m2/yr and the Vancouver Zero Emissions Building Plan has a 2030 limit of zero kgCO2e/m2/yr; even in 2050 the NYC target is 15 kgCO2e/m2/yr for all existing buildings. It is always easier to achieve reductions in new construction, but this comparison also highlights the importance of indirect emissions.

In Vancouver, the electricity supply is largely from green sources, facilitating near-zero emissions from buildings that electrify their heating and hot water systems (of course, this assumes that British Columbia continues to expands the green electricity supply and expand grid capacity with growing electricity demand). In Toronto, the GHG intensity of the electricity grid is higher than in Vancouver and the climate is more severe, and the GHGI targets for buildings reflect this. The chart below compares the heating and cooling degree days for Vancouver, Toronto and New York City, as well as the local GHG intensity of electricity in each city.

While decarbonization of the electricity grid is actually proceeding at a respectable rate in many other jurisdictions, the electricity supply to NYC is still primarily derived from fossil fuels. However, in June 2019, state legislators introduced a bill that would require the state electricity supply to be 70% renewable by 2030 and 100% renewable by 2040, which would go a long way towards helping buildings in New York City meet their emissions targets. Still, there will be considerable challenges to upgrading the local electricity grid within NYC to accommodate considerably higher use of electricity in buildings and transportation. There will continue to be a role for other sources and carriers of green energy such as green gas (including biogas and hydrogen) and low carbon heat networks to capture waste heat and tap other local renewable energy sources.

Decarbonizing the existing Con Edison steam system is a pressing challenge to meet 2030 targets. This will be particularly difficult in NYC, where the prospect of shutting down streets to upgrade or replace the vast and aging steam distribution infrastructure is untenable. Decarbonizing steam is possible through the use of biogas, biomass, and local waste, but there will be challenges finding sites for local energy generation.

A Modest but Important First Step

Overall, the NYC legislation appears to strike a fair balance between near-term action on buildings with exceptionally high GHG emissions and more sweeping changes across the majority of the city’s buildings by 2030. It allows time for building owners and vendors to adapt to the new requirements and for systemic changes in the energy supply to take place. Reducing the GHG emissions from existing buildings in a city as large as New York is a massive and worthwhile undertaking. I will be watching with great interest to see what policy direction other cities, such as Vancouver and Toronto, take to address emissions from existing buildings.

– Sonja Wilson